I graduated from Macalester College with my physics degree, lounged around doing nothing but baking brownies, watching tv, and preparing for a friend’s wedding until mid-July, when I jumped straight into my PhD work. I’m currently funded on two projects, so I got to try a little bit of both.

The first project involves field work in Greenland! I didn’t get to go this summer because the cruise was during Math Camp (not my choice), but I did get to learn all about the project and look at some pretty neat satellite imagery.

Why do we care about Greenland? No matter what your thoughts are on why climate change is happening, our climate is changing – the loss of mass from the polar ice sheets (both poles) has tripled in the last twenty years (Straneo et al., 2013 and references therein). The Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS) mass loss seems to be due to two processes: high air temperatures melting the ice from the surface, and an unexpected rapid speedup, retreat, and thinning of glaciers that started in the 90s.

Why do we care that the ice is melting? If you’ve ever seen the film The Day After Tomorrow, you’ve enjoyed an over-dramatized, scientifically suspect version of the results. One of the few things that they got right was that melting ice from Greenland means a larger amount of cold freshwater entering the North Atlantic near areas that affect global ocean circulation. I won’t go into the specifics right now, but the film got it wrong on how it would affect the circulation, and then they went crazy with the rapid climate change and insane storms. The freshwater input is near where deep water masses form, which I will do a blog post on at a later time, but for now, you can read the Wikipedia article if you want.

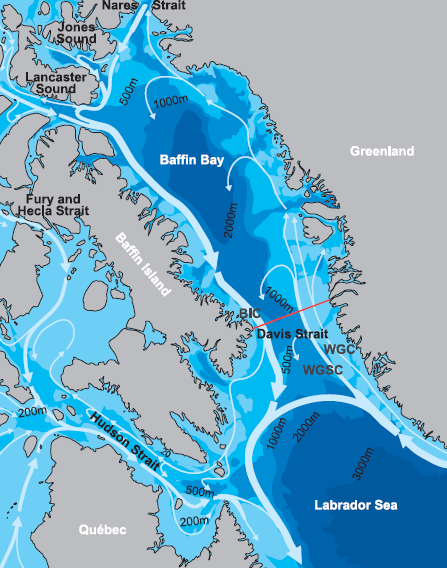

What is causing this rapid melting of glaciers? One of our hypotheses is that warm, salty water from the North Atlantic (Atlantic Water, or AW) is making its way up the western coast of Greenland in the Western Greenland Current (WGC), just like the East Greenland Current does on the other side. Does that water make it past the sills that block access to the fjords and their glaciers? And how do we tell?

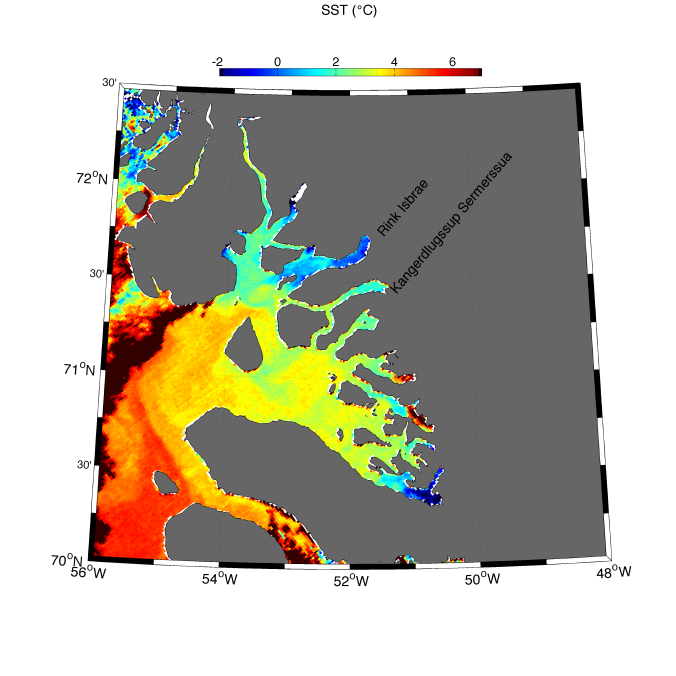

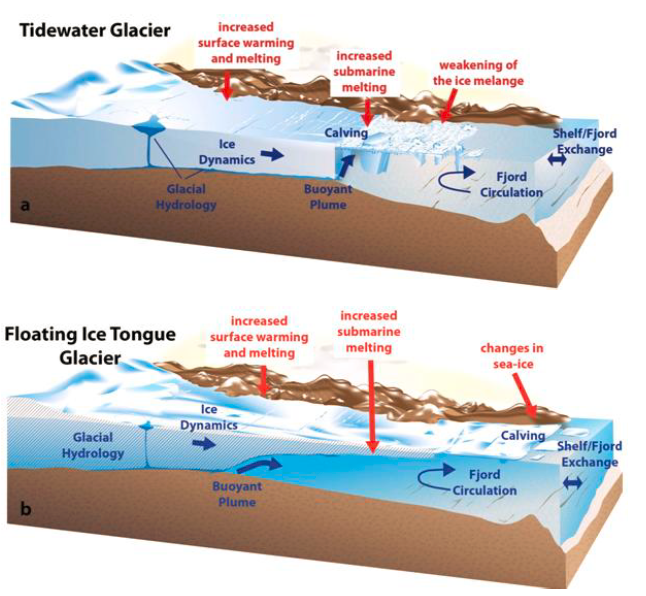

Well, we’re looking at two different marine-terminating glaciers in central western Greenland, Rink Isbrae and Kangerdlugssup Sermerssua. What are marine-terminating glaciers? They are glaciers that meet the ocean at their ends, usually in a fjord. This glacier “terminus” (just a fancy word for end) is where calving happens, and where the ocean water can meet and melt the glacier directly.

Types of glaciers marine-terminating glaciers, and different ways that they lose ice mass. From Straneo et al., 2013

The research cruises collect a variety of data about the temperature, salinity, and current velocities in the fjords, while I look at satellite data of sea surface temperature (SST). We don’t know much yet, but here’s a really good satellite image of SST. I’ll let you know more as we figure it out.